|

# 2022-06-21 - There Is A Way by Sat Santokh

# Chapter 1, My Roots

When my grandfather was over 60, he was severely burned in a fire.

After being in the hospital for a month or so, they told him that he

would never walk again. He immediately asked to be sent home. Then,

whenever he was alone, he would flop himself out of bed and crawl

around the house and up and down the stairs. Within a month he was

back on the truck with my father.

The Oz books were so real to me that when I decided to be a pilot at

age eight, it was so I could cross the uncrossable desert and take my

place in Oz along with Dorothy, Trot, Captain Bill, and Buttonbright.

At ten, I became an atheist, but, I know realize, a Jewish kind of

atheist, where I frequently lectured the God I did not believe in for

the world's ills and disasters, alternating back and forth from

denial of God to anger with God.

I felt an ever increasing degree of franticness within the peace

movement in our responding to one crisis after another, which, for

me, peaked with the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, when it

became appallingly clear that we were at the brink of World War III.

I felt this possibility so strongly that after taking part in an

8,000-person protest march to the United Nations at the height of the

crisis, I solemnly bade goodbye to my friends, telling them that we

might not see each other again, and went home to prepare for the end.

Most of my friends felt that I was being excessively melodramatic.

However, many years later, in 2006, at a meeting of the ministers of

defense of the various countries involved in the Cuban crisis

convened by Robert McNamara, who had been the US Secretary of Defense

at the time of the confrontation, it was revealed that the situation

had been just as dire as I thought. McNamara himself had bid his

family goodbye that night, telling his wife that they might not see

the morning. It turned out that the decision whether or not to fire

the Soviet missiles that were based in Cuba was entirely in the hands

of the Soviet captain in charge. If the United States Navy had fired

a shot to stop the Soviet vessels cruising towards Cuba from crossing

the line in the ocean that President Kennedy had stipulated, the

Soviet captain would have opened fire on the United States with

nuclear missiles, and the unimaginable Armageddon would surely have

begun.

# Chapter 2, From Psychedelics to Spiritual Practice

By 1966, I felt burned out. I had been working over 70 hours a week

with no breaks, maintaining regular daytime office hours, and then

going to meetings, or speaking opportunities just about every night

and on the weekends. From my perspective, there was no progress at

all. Yes, the Peace Movement was growing exponentially, but so was

the war.

Michael Rossman, one of the founders and important leaders of the

Free Speech Movement at University of California Berkeley began to

speak of LSD as potentially the most revolutionary way to shift our

collective consciousness. I attended the big "Human Be-In" that took

place at the Polo Fields in Golden Gate Park, with Alan Ginsberg,

Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert (later Ram Dass), the Grateful Dead,

Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver, and other beat and hippie notables.

Having become disillusioned with my role in the Peace Movement, I

resigned from the WRL and became the treasurer, chief cook, and

bottle washer for this committee. I was given an office at 715

Ashbury, the Grateful Dead office building. Our committee began to

organize frequent free concerts either in Golden Gate Park or the

Panhandle, and as I was our (unpaid) staff person, I became the

liaison with the San Francisco Park Department, arranging for permits

and all the other details.

We must have talked for at least six hours straight that first night,

staying up until the early hours of the morning. Somewhere in the

course of the night, I asked him what I should do with my life. He

said "Shine, one must let one's light shine." I asked, "What do you

mean?" And he replied with one simple sentence that I have carried

throughout my life ever since: "Be a radiant example of how to live

on the planet."

... when I took my last acid trip... in May 1970. This experience

was very different from all that had preceded it. Every direction my

mind would go would result in my perceiving the same message: "There

is nothing further to be gained in this direction, everything depends

on your daily action." It was time for a change. I decided that I

needed to find a teacher.

There is an old spiritual teaching that when you are ready to find

your teacher, your teacher will come. I attended an event called

"The Holy Man Jam at the Family Dog on the Great Highway." It was a

transitional event at the close of the hippie era, with many

spiritual leaders including Yogi Bhajan, Swami Satchidananda, Pit

Vilayat, Rabbi Shlomo Cattebach, Baba Ram Dass, Stephen Gaskin, and

others. Just prior to attending the event, I had concluded that in

order to do the work before me, I needed to find a way to allow great

power and energy to flow through me without the energy being wrongly

directed by flaws in my ego or personality; to not crave or seek

power, but have it flow through me in service of humanity. When Yogi

Bhajan spoke, I felt the immensity of the energy flowing through him,

and how easily it flowed without seeming to be distorted by his ego.

One day I was sitting alone on a couch with him when he said, "Why

don't you give up all this nonsense?" I said that I would like to.

He placed his hand on my head and I felt very comfortable and secure,

like a little child with his father. I asked him what to do for the

morning practice, and he told me to chant Sat Nam...

In this short period, I stopped smoking cigarettes and grass and

stopped eating meat.

Then there was the continuing experience of my early morning sadhana

practice. Robin and I were at the point that the simple act of

sitting down to do sadhana was profound in itself.

# Chapter 3, How I Came To Be A Healer

About half a year after returning to the Bay Area in late 1970, I Was

in charge of a large 17-bedroom Kundalini Yoga ashram overlooking Mt.

Tamalpais, with 25-40 residents. For some years afterward, I wholly

immersed myself in yoga practice--morning sadhana with everyone, one

or two yoga classes during the day, and an evening practice as well.

I had jumped onto the "Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan" (as

we described it in those days) practice with both feet, as it were,

with the result that I was a bit of a fanatic in the early years all

through the 70s and into the 80s. I had decided that Yogi Bhajan was

my teacher and that I would do what he said in pretty much all

things. He named our yoga organization "3HO," which stood for

"Healthy, Happy, Holly Organization," telling us that if we followed

the practice, we would first become healthy, then happy, and then

holy.

As the name Sat Santokh, which was given to me by Yogi Bhajan,

translates as "true contentment," I had thought that my work was to

find contentment in whatever circumstance I found myself. Yet,

clearly, I was not content...

Towards the end of that winter, I decided that if even emulating

Ghandi would not make me feel "good enough," then there was no hope

of ever feeling that way, and the only solution was to find a way to

accept myself as I was, flaws and all. Finally, after going over all

this every day for months, I was able to accept myself as "good

enough" with all my faults, flaws, needs, and desires. Later, I Was

to discover that this was just the beginning of learning to accept

myself.

I wanted to be pulled forward by my vision of service rather than

being pushed by my fear of failure or need for personal benefit. I

had observed that for the most part, as an energy-dynamic, "pulling"

works much better than "pushing"... Another way of saying this is

that I was learning to "be in the flow," which is generally not

possible when struggling or in fear.

Through the influence of Joanna Macy, who was on our board and helped

lead workshops in the first year, and her Despair and Empowerment

workshops, we started to ask deep questions at Creating Our Future

workshop sharing sessions, such as:

* How do you feel about yourself?

* How do you feel about your parents?

* How do they feel about you?

* What do you like about yourself?

* What do you not like about yourself?

* What are your fears about the state of the planet?

For many years I thought doing a strong daily yoga or other spiritual

practice would heal and clear up these wounds, but I have not found

that to be the case, either for myself or for most people of my

acquaintance, and I know very large numbers of people who are

committed to such work. Spiritual practice is profoundly helpful and

important, but it is not enough, in most cases, to heal the wounds of

life.

# Chapter 4, Self Worth

I do not know of any way to raise a child and never make a mistake

There will be wounds. The best a parent can do is let the child know

that they are loved without condition, that they do not have to prove

or accomplish anything to be loved and listened to.

I recognize that "self-demoting feedback loop" is a challenging

phrase, but it is the most apt and concise one that I can come up

with to describe an all-too-frequent phenomenon. The term applies to

almost all addictive behavioral patterns, whose root cause is a

subconscious wound-story resulting in a compulsion to punish

oneself...

The wounded self stays present in the subconscious indefinitely

unless there is some form of intercession or healing.

The subconscious exists only in the present "now." When a person

believes that they do not deserve to be happy, to do well, to be

well, or that they deserve to suffer, they set out to prove and

justify that belief over and over again. This is not a consciously

made choice, but is directed by the subconscious.

There are many defense-mechanisms that develop in childhood that may

be needed for survival at the time, but might become serious

impediments as one matures.

Wherever our wounds may come from, they leave us with a story we

believe about ourselves, and it is that story that determines what is

and is not possible for us.

It is important to understand that the wound is not the event that

happened, but its impact on our sense of self. The wound is to our

psyche, our sense of identity. In healing work, we cannot change or

take away what happened. What we can change is the story that was

implanted in our subconscious as a result of what happened.

For each of us, there are habits, jobs, and relationships that are

demoting and ones that are promoting.

Why go to such places? Why bring up such horrible memories? The

reality is that the wounds are there. They have been planted in the

subconscious. For healing to take place, there needs to be some

context within which to access the wounded self in the subconscious,

so that the story that the wounded self came away with can be heart

and changed, and the person can feel healed.

These wounds, then, are stories, conclusions we come to believe about

ourselves that are based on wounding circumstances, and also based on

the ways in which we seem to be programmed to react.

# Chapter 5, The Human Condition

Insofar as I can tell, we are all wounded in one way or another,

generally with multiple wounds. Yet it seems that most people do not

seem to be aware of their inner wounds, but instead there are beliefs

about the self and what is possible or not possible in life that are

results of being wounded. These beliefs generally become axiomatic,

meaning, "obviously true and therefore not needing to be proved."

One of my prime reasons for writing this book is to establish and

make clear the role and importance of inner wounds in our lives, and

to show that these wounds can be healed. It is important to know

that the wounds are stories, and as such they are mutable, for

stories can be changed, and one's quality of life can change

dramatically. I hope to create a shift in our collective

understanding about the possibility of healing our wounds, and our

collective understanding about what we can aspire to in our lives.

# Chapter 6, Healing the Wounds of Life

One of the things I say quite often to prospective journeyers at the

beginning of the workshops is: "If you are thinking of something that

you do not want to share, something that you do not want to mention,

that you do not want anyone to know about, then that is the most

important thing for you to bring up at this time. It is what you are

here to deal with. This is the place and time. You may not have

this opportunity again."

They may have tried to say these [positive, uplifting] things to

themselves many times in the past, but there is virtually no

connection between the cognitive mind and the subconscious self, it

does not help much. I have found that generally one cannot do this

by oneself. To simultaneously be in your conscious mind trying to

guide yourself, and in your subconscious mind being guided, is a big

stretch, and it is very rare that one can lead oneself into such a

deep place.

One of the critical elements of the healing is the creation of a

space in which a person can say virtually anything that they are

deeply ashamed of, and have it received with love, understanding, and

compassion. Most of us have something in our past, or present, that

we are deeply ashamed of, about which we feel that if others ever

knew this about us, we would be judged and rejected. One of the

results of holding such beliefs is that we conclude within our

subconscious that we are no good and that we must hide this

no-goodness from others. So when we say these things in a group of

peers and there is no negative reaction at all, but only a palpable

love felt by all, this in itself is profoundly healing.

This tender new plant is their new sense of self, a self that

deserves to love and be loved, to trust and be trusted, and to

succeed in life. The weeding, feeding, cultivating, and nurturing is

usually done by adopting a yoga and/or meditation practice in which

they regularly repeat to themselves the phrases that they record. In

addition, I ask them to practice self-forgiveness, and to talk about

its profound importance in cultivating their inner garden and keeping

it healthy. This homework is really a critical part of the process.

# Chapter 7, About Myself as a Healer

I have not yet found any meaningful answer to why God allows bad

things to happen. I have seen many attempts at providing that

answer, from within myself and from various religious and spiritual

perspectives, but for me none of them hold up to examination, the

reasoning is always flawed. I have come to accept simply not knowing

and not understanding; it is as it is, and I do not know why.

Some twelve years later I found myself in an interesting discussion

with two long-time friends at the 2005 Kundalini Yoga Summer Solstice

Celebration, in which one of them said, "Sat Santokh, here you are a

devoted leader and practicioner of what is essentially a form of

Bhakti Yoga, yet you are quite angry with the object of your

devotion. How can you ever realize the fruits of that devotion if

you continue to harbor that anger?" [Better to be angry with God

than to be angry with a human being. God can take it.]

I realized that sitting in judgment of God pretty much throughout my

life profoundly limited my capacity to love God, and also, perhaps,

my capacity to love myself.

I led the first training on how to guide Self Worth workshops in

Ireland in late 2007. By the end of that training, I saw that I

could pass on this work; that it was not just going to be confined to

me. Second, just before the end of the training, I was led on my

first true Self Worth journey by two of the students, which deepened

and expanded the healing I had previously experienced.

I thought, "If you cannot trust, you cannot really be open to life or

be present in life. I would rather trust and be betrayed than never

trust at all."

# Chapter 8, Anger and Hate

I wish to assert here that from my perspective, any corporal

punishment of children is physical abuse.

In most children, the first and primary reaction to being physically

punished is fear.

The fear becomes internalized, and the belief that the world is not a

safe place becomes entrenched. [Is the world really such a safe

place though?]

I have been studying and thinking about hate and anger in society for

a long time, their relation to war, xenophobia, and the mostly

dysfunctional ways we govern ourselves, live our lives, and conduct

business around the planet. I have come to believe that... any

doctrine that preaches hate of some group of "others"--are all rooted

in the fear, anger, and hatred activated by abusive childhood

experiences. And I believe that the abuse of children and its

expression as anger and hate in adults has profound implications for

the state of the world today.

# Chapter 9, Consequences

There seems to be not a single exception. From Sumer to Egypt to

China, from ancient India to pre-Columbian America, from Athens to

Rome, children were hit. Oral and then written traditions

universally came to postulate this behavior in proverbs that are

found on every continent.

Between the seventh and sixth centuries BC, about 2,500 years ago,

Spartan boys were taken from their homes at age seven to begin

military training. It was believed that they needed to be removed

from their mothers' care in order not to be "coddled." Instead, they

experienced a very harsh discipline. They were regularly flogged and

taught not to cry out. The older boys beat the younger boys as a

regular part of the program. They were required to steal food and

clothing in order to have food to eat or shoes on their feet, and

would be severely punished if caught; punished, not for stealing, but

for being caught.

The example created by the Spartans at Thermopylae giving their lives

in sacrifice while only 300 of them were able to hold off the huge

Persian army for several days, has resounded through military history

throughout the world ever since. Over the 2,500 years since then,

military leaders and heads of state, wishing to have the best

possible soldiers so they could win their wars, have frequently come

to the conclusion that they needed to emulate the Spartan way of

training men and boys in order to create Spartan-like soldiers, even

to this day.

Sparta was the only Greek city-state that had a professional army; at

the time of this battle, the only occupation for Spartan men was

warfare. A slave class called "Helots," composed primarily of the

conquered people of neighboring city-states, did all the farming and

artisinal work to provide food, clothing, and material goods for the

Spartans.

Prior to Napoleon, Frederick the Great had developed the most

powerful and well-disciplined army Europe had ever seen, and had made

Prussia into a great European power. However, Napoleon easily

crushed the Prussian army in two major battles in 1806, a humiliating

defeat for King Frederick William III, grandson of Frederick the

Great, which led to the subjugation of the Kingdom of Prussia to the

French Empire. Casting about for how to rebuild his armies,

Frederick William III, impressed by the discipline, competence,

fierceness, willingness if not eagerness to sacrifice their lives,

and patriotism of the Spartan army at Thermopylae, decided to modify

the Prussian Corps into a training program for boys and young men

modeled directly upon the Spartan Agoge.

Interestingly, we find that both Britain and the United States

modeled their education systems on this Prussian education system.

Many educational pioneers throughout Europe and the United States

thought that the Prussians had developed the best education system

for disciplining and educating students so that they would become

efficient and obedient workers and soldiers. Even the idealistic

Herman Mann (1796-1859), "The father of American public education,"

went to Prussia to study their system.

Spartans believed that they were descended from the Dorian tribe,

which is generally thought to have conquered most of what we know

think of as Greece, between 1100 and 1000 BCE. The Dorians were not

considered to be a particularly cultured people, but they did

introduce the iron sword, with which they conquered the Minoan and

Mycenaean peoples. The Spartans, who were dedicated to being a

warrior people, took pride in their presumed Dorian ancestry. In the

mid-1800s, the belief began to enter into the culture of the Germanic

and Prussian peoples as they began to idealize and mythologize

Sparta, that they too were descended from the Dorians, a belief which

was tied to their developing notion of Aryan superiority.

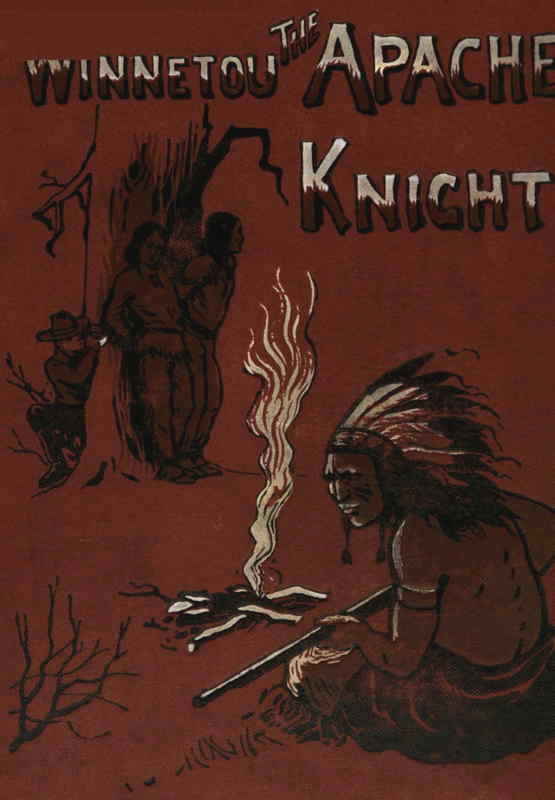

Around this time in Prussia/Germany, a fascination with the "noble

savages" of the New World also began to develop. Their Spartan

mythology expanded to include the belief that these "noble savages"

were actually descendants of Dorian tribes that had emigrated to the

New World, and that, they shared the same racially pure warrior

bloodstream as the Germanic people. This fantasy about Native

Americans was catapulted throughout Germany via the novels of Karl

May (1842-1912), a very popular German author whose books have sold

200 million copies, and to whom we are indebted for the Germanic myth

about "An Indian brave who knows no pain."

|