| WINDOW TAX

2024-04-28

...IN ENGLAND AND WALES

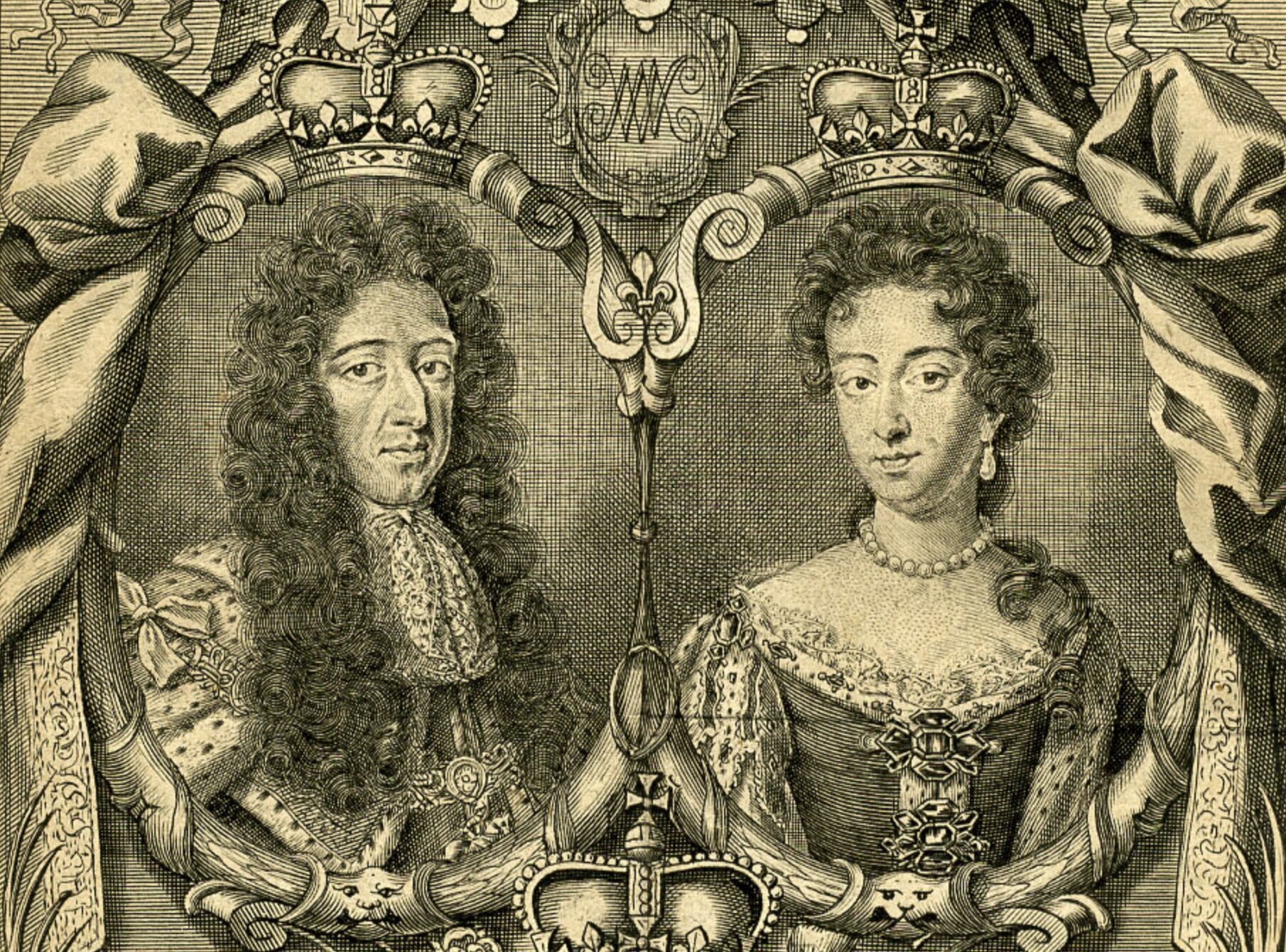

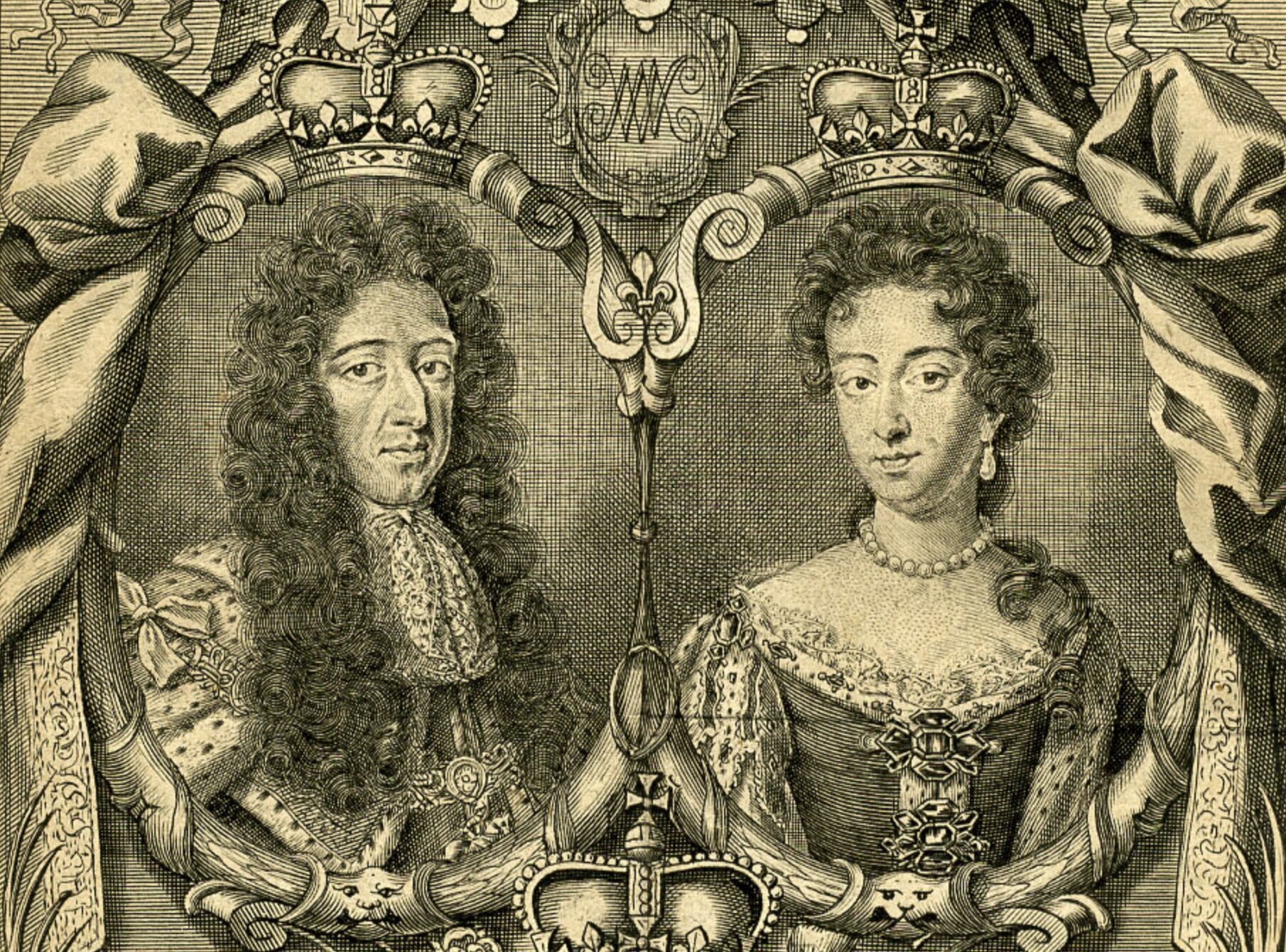

From 1696 until 1851 a "window tax" was imposed in England and Wales

(Following the Treaty of Union the window tax was also applied in Scotland,

but Scotland's a whole other legal beast that I'm going to quietly ignore for

now because it doesn't really have any bearing on this story.). Sort-of a

precursor to property taxes like council tax today, it used an estimate of the

value of a property as an indicator of the wealth of its occupants: counting

the number of windows provided the mechanism for assessment.

|

|

|

|

(A particular problem with window tax as enacted is that its "stepping", which

was designed to weigh particularly heavily on the rich with their large

houses, was that it similarly weighed heavily on large multi-tenant buildings,

whose landlord would pass on those disproportionate costs to their tenants!)

|

|

|

|

Why a window tax? There's two ways to answer that:

* A window tax - and a hearth tax, for that matter - can be assessed without

the necessity of the taxpayer to disclose their income. Income tax, |

| Pie chart illustrating the sources of tax income in the UK in 2008. |

| , was long considered to be too much of an invasion upon personal privacy

(Even relatively-recently, the argument that income tax might be repealed as

incompatible with British values shows up in political debate. Towards the end

of the 19th century, Prime Ministers Disraeli and Gladstone could be relied

upon to agree with one another on almost nothing, but both men spoke at length

about their desire to abolish income tax, even setting out plans to phase it

out... before having to cancel those plans when some financial emergency

showed up. Turns out it's hard to get rid of.).

* But compared to a hearth tax, it can be validated from outside the property.

Counting people in a property in an era before solid recordkeeping is hard.

Counting hearths is easier... so long as you can get inside the property.

Counting windows is easier still and can be done completely from the outside!

|

|

|

|

...IN THE NETHERLANDS

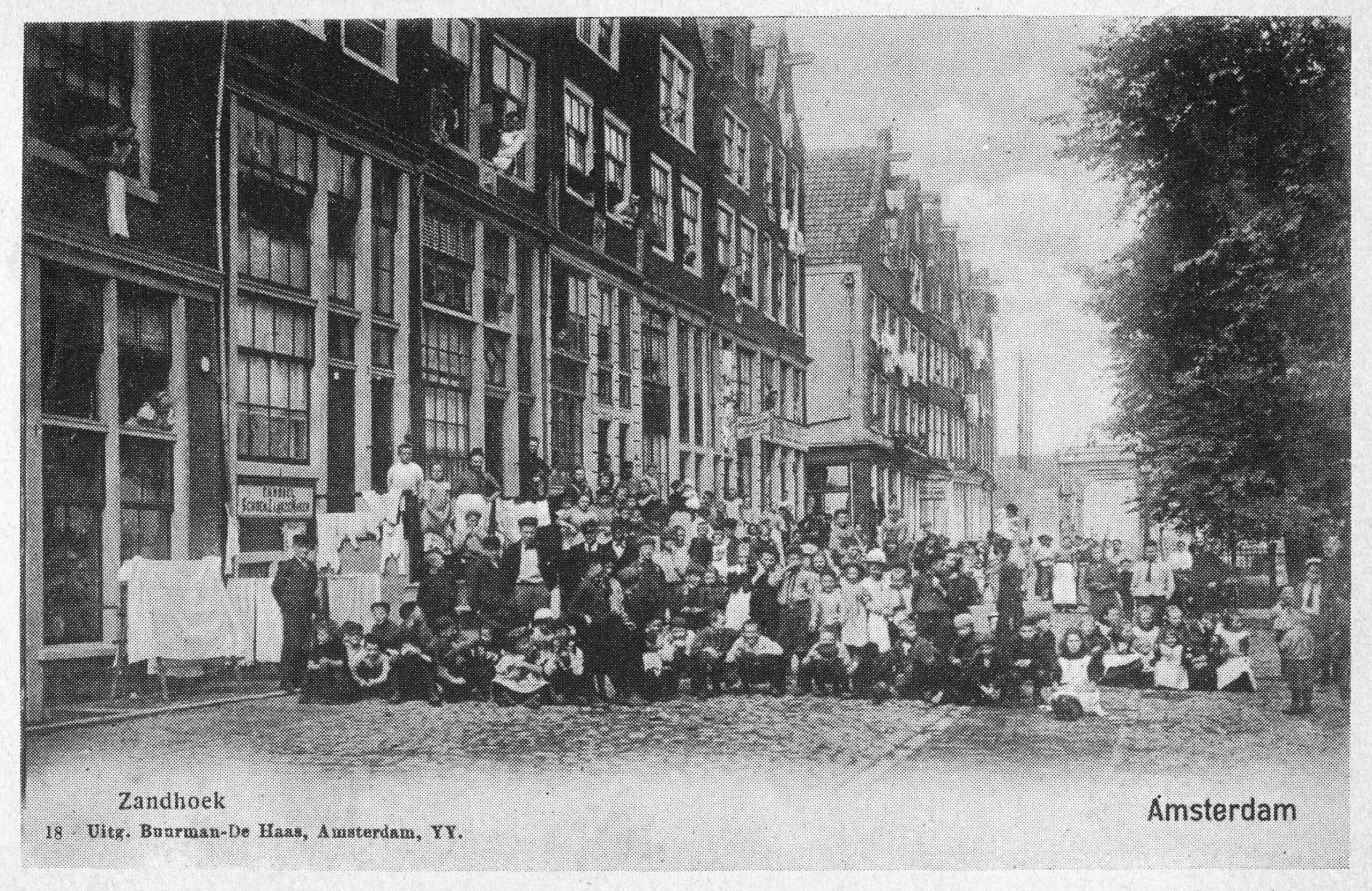

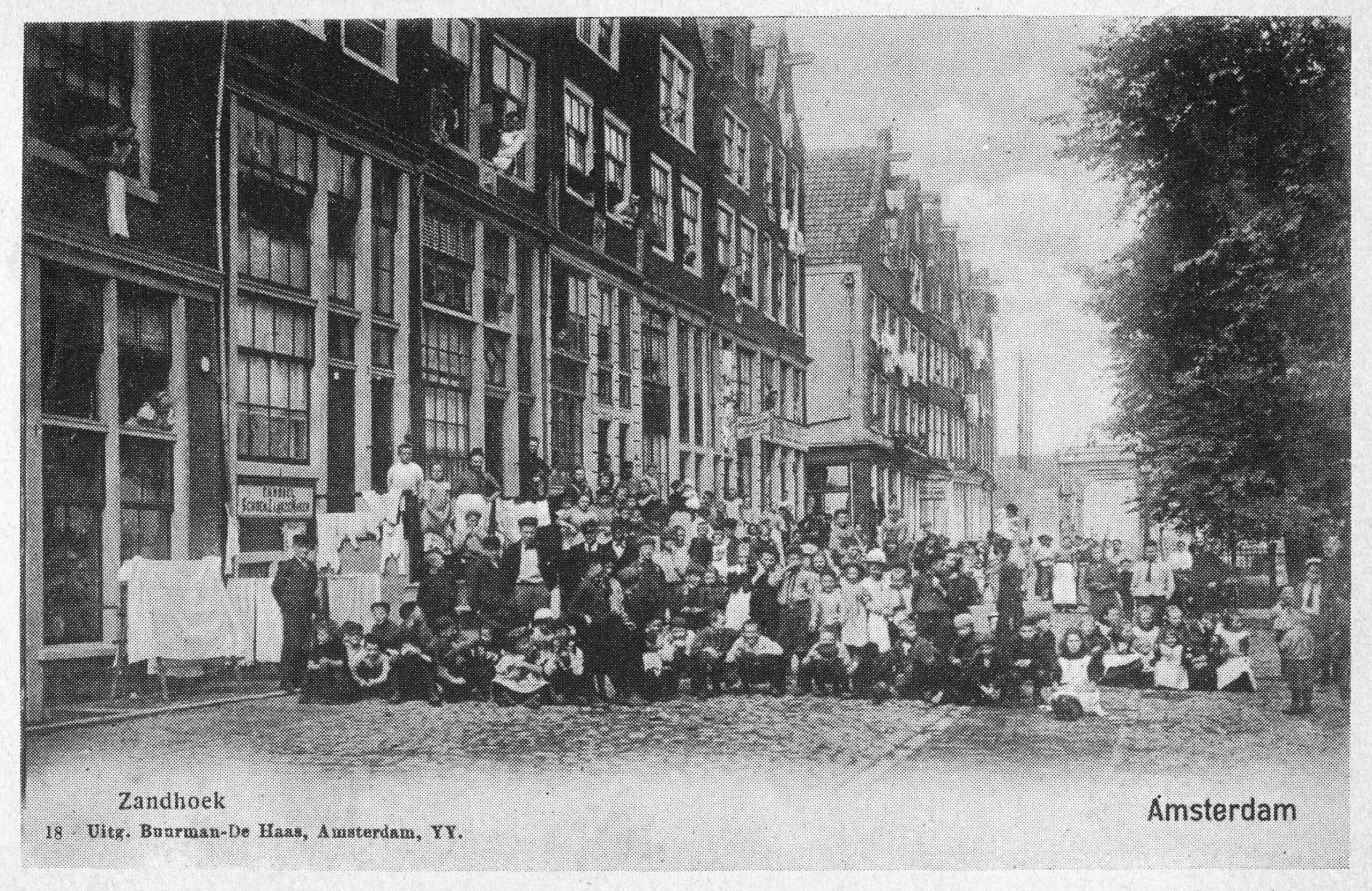

I recently got back from a trip to Amsterdam to meet my new work team and get

to know them better.

|

|

|

|

One of the things I learned while on this trip was that the Netherlands, too,

had a window tax for a time. But there's an interesting difference.

The Dutch window tax was introduced during the French occupation, under

Napoleon, in 1810 - already much later than its equivalent in England - and

continued even after he was ousted and well into the late 19th century. And

that leads to a really interesting social side-effect.

|

|

|

|

Glass manufacturing technique evolved rapidly during the 19th century. At the

start of the century, when England's window tax law was in full swing, glass

panes were typically made using the crown glass process: a bauble of glass

would be spun until centrifugal force stretched it out into a wide disk,

getting thinner towards its edge.

The very edge pieces of crown glass were cut into triangles for use in leaded

glass, with any useless offcuts recycled; the next-innermost pieces were the

thinnest and clearest, and fetched the highest price for use as windows. By

the time you reached the centre you had a thick, often-swirly piece of glass

that couldn't be sold for a high price: you still sometimes find this kind

among the leaded glass in particularly old pub windows (You've probably heard

about how glass remains partially-liquid forever and how this explains why old

windows are often thicker at the bottom. You've probably also already had it

explained to you that this is complete bullshit. I only mention it here to

preempt any discussion in the comments.).

|

|

|

|

As the 19th century wore on, cylinder glass became the norm. This is produced

by making an iron cylinder as a mould, blowing glass into it, and then

carefully un-rolling the cylinder while the glass is still viscous to form a

reasonably-even and flat sheet. Compared to spun glass, this approach makes it

possible to make larger window panes. Also: it scales more-easily to

industrialisation, reducing the cost of glass.

The Dutch window tax survived into the era of large plate glass, and this lead

to an interesting phenomenon: rather than have lots of windows, which would be

expensive, late-19th century buildings were constructed with windows that were

as large as possible to maximise the ratio of the amount of light they let in

to the amount of tax for which they were liable (This is even more-pronounced

in cities like Amsterdam where a width/frontage tax forced buildings to be as

tall and narrow and as close to their neighbours as possible, further limiting

opportunities for access to natural light.).

|

|

|

|

That's an architectural trend you can still see in Amsterdam (and elsewhere in

Holland) today. Even where buildings are renovated or newly-constructed, they

tend - or are required by preservation orders - to mirror the buildings they

neighbour, which influences architectural decisions.

|

|

|

|

It's really interesting to see the different architectural choices produced in

two different cities as a side-effect of fundamentally the same economic

choice, resulting from slightly different starting conditions in each (a

half-century gap and a land shortage in one). While Britain got fewer windows,

the Netherlands got bigger windows, and you can still see the effects today.

...AND SOCIAL STATUS

But there's another interesting this about this relatively-recent window tax,

and that's about how people broadcast their social status.

|

|

|

|

In some of the traditionally-wealthiest parts of Amsterdam, you'll find houses

with more windows than you'd expect. In the photo above, notice:

* How the window density of the central white building is about twice that of

the similar-width building on the left,

* That a mostly-decorative window has been installed above the front door,

adorned with a decorative leaded glass pattern, and

* At the bottom of the building, below the front door (up the stairs), that a

full set of windows has been provided even for the below-ground servants

quarters!

When it was first constructed, this building may have been considered

especially ostentatious. Its original owners deliberately requested that it be

built in a way that would attract a higher tax bill than would generally have

been considered necessary in the city, at the time. The house stood out as a

status symbol, like shiny jewellery, fashionable clothes, or a classy car

might today.

|

|

|

|

Can we bring back 19th-century Dutch social status telegraphing, please? (But

definitely not 17th-century Dutch social status telegraphing, please. That

shit was bonkers.)

LINKS

|

| Window Tax on Wolverhampton Archives & Local Studies, as archived by archive.org. |

| BBC News article about reasons for bricked-up windows. |

| My blog post about changing teams at work. |

| My blog post about coming up with icebreaker games and playing them with my new team. |

| Jacqueline Alders' blog post about window taxation in the Netherlands. |

| A series of photos demonstrating crown glass production. |

| Article debunking the "glass is liquid" myth. |

| Pet Shop Boys - What Are We Going To Do About The Rich? |

| Wikipedia article about tulip mania, a 17th-century Dutch social status telegraphing phenomenon. |